Journal

Interview: Helen Kitson

In conversation with artist Helen Kitson.

Can you describe your journey into the arts?

I’ve always had an interest in visual art, but literature was my passion from a very young age. When my children were young, through online friends, I discovered the work of mixed media artists such as Lynne Perrella, Anne Bagby and Juliana Coles. For the first time since I’d left school I experimented with paint and other media. It was quite mind-blowing to me that it was possible to create art without having any conventional fine art skills. Life got in the way, as it often does, but many years later I decided, having studied a module on Renaissance art for my first degree, to study for an MA in art history.

I had vague ambitions to work in a gallery/museum setting, but the work I did for the final module of my MA was crucial in shaping my attitudes towards art. The aim of this module was to reconsider “objects and makers, and art well beyond the gallery context”. I realised that art wasn’t just about valuable paintings hung in famous galleries. I fell down numerous rabbit holes and at some point I discovered the work of Kurt Schwitters, and that changed everything.

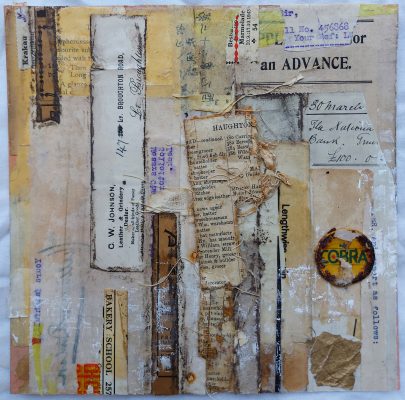

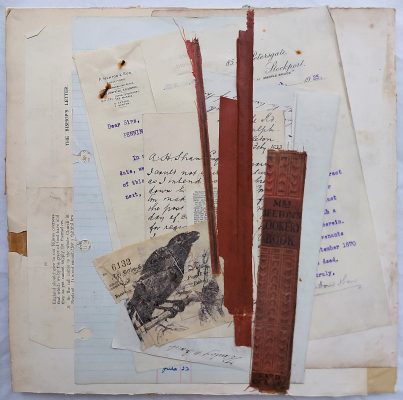

I can’t draw or paint and have no great desire to do so. What I learned from Schwitters, and all the other amazing collage artists I discovered through him, is that it’s possible to create exciting, original art without those traditional skills. It’s a different sort of art, but with the same engagement with the materials used, and the same attention to composition and creating visual impact. Schwitters’ work was the first I’d seen that made me think not just that I could do something like this, but that I want to do something like this. It freed me up to experiment, to let go of all the preconceptions I had about Art.

Can you talk about historical and contemporary influences on your work. You have cited work from Kurt Schwitters, El Lissitsky through to Allan Bealy. And while they are all unique, there are certain traits or tropes that underpin this work.

I’m drawn to artists who push the boundaries of their practice through constant experimentation, and also to artists who understand the importance of design and the artistic potential of typography.

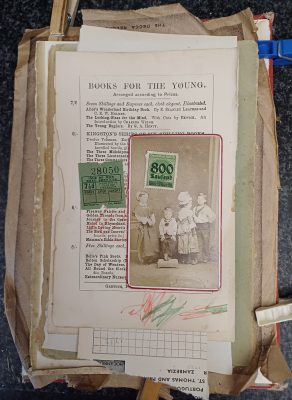

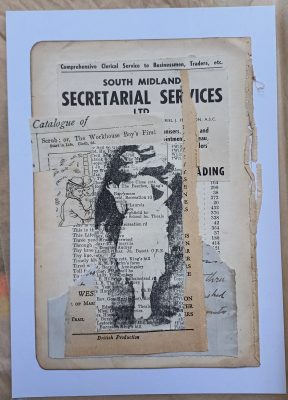

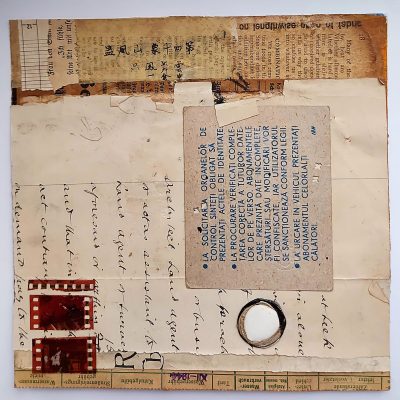

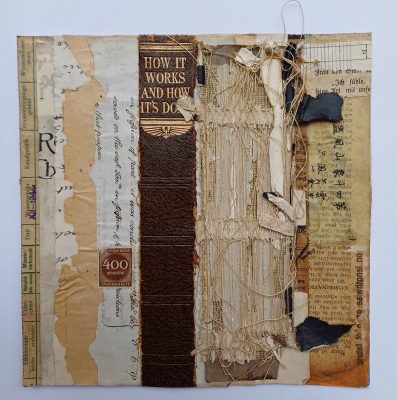

I use vintage materials almost exclusively in my work, and I’m aware of the temptation to produce something that is kitschy or overly nostalgic. The artists I admire reinterpret images that already exist to explore the materials used: the textures and colours as well as any ‘messages’ they might carry. Collage for me is about finding connections between disparate elements, juxtaposing them in a way that is sometimes harmonious, sometimes deliberately jarring. The collage artist decides which connections to make (sometimes deliberately, sometimes intuitively, sometimes as a result of happenstance), and that’s what makes it exciting to me as an art form and what excites me in the work of other collage artists.

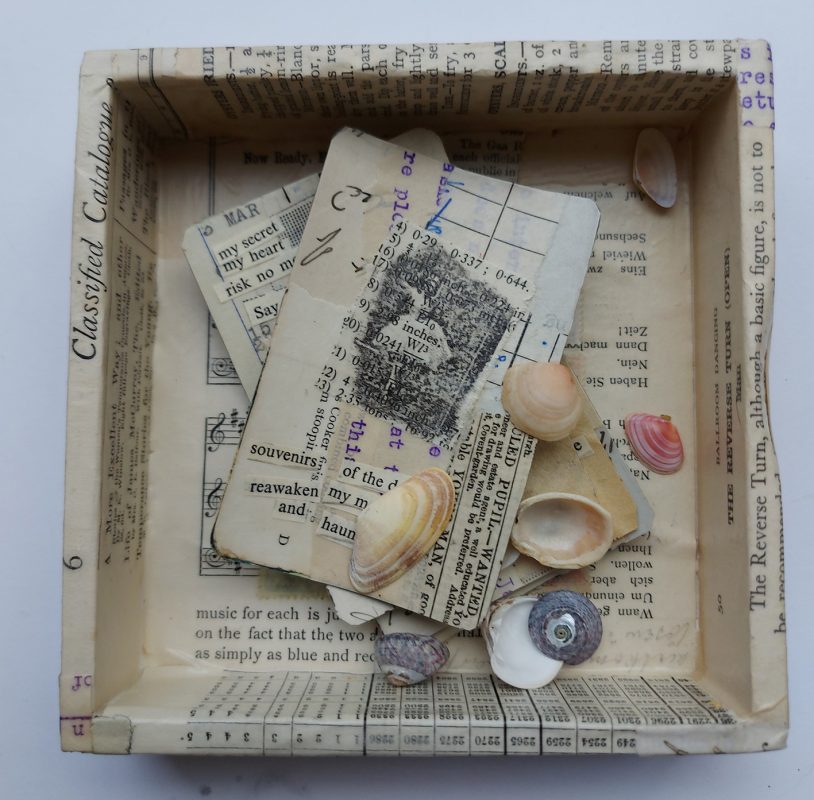

Some of your more recent work include notions of containment (boxes that hold items) through to boxes that use compartmentalisation or collection or topologies of items, for example shells. Can you talk about this process and what you are trying to achieve.

It’s no secret that my boxes are very much influenced by the work of Joseph Cornell. Cornell’s assemblages are often very considered, very beautiful and sublime, and nostalgia is often foregrounded. Sentimental nostalgia is something I try to avoid in my collages, but I allow it more leeway in the boxes.

I’ve always been fascinated by the potential of boxes to carry secrets, and memories. This I think stems from childhood memories associated with my grandmother. She kept her jewellery in a chocolate box – the old fashioned sturdy kind you don’t see anymore – and I loved rifling through her treasures whenever I visited. Her jewellery was mostly paste, Bakelite, rusty hat pins, metal badges from my grandfather’s days in the KSLI during WW1, but it was all treasure to me. She also had a tin in which she kept sweets, the lid of which was encrusted with varnished seashells. I remember how much I enjoyed running my hands over the shells, enjoying how they felt as much as how they looked. As an adult, I have a ‘memory box’ that is a simple wooden box filled with things that remind me of people I care about, or have cared about: Valentine cards from barely-remembered loves, faded snapshots, the plastic wristbands from when I was in hospital having my children.

I think all of these feelings also connect with the idea of the reliquary, the beautiful object made to hold things considered holy. I grew up in a non-religious household and have remained an atheist, but have always had an interest in religion, and in particular Catholicism. One of the highlights of a trip to Munich was seeing firsthand the jewelled skeleton of Saint Munditia in St Peter’s Church, contained in a glass case behind a locked wrought iron gate. So there’s also a sense of the forbidden – the locked box, and the urge to find out what’s inside it, which is I think a very human compulsion.

Can you talk about the process of making books as opposed to making objects.

Although I began my literary journey as a poet, I always wanted to write novels, but after having two published I was burned out, it had all become a bit of a grind. I think making art is closer to poetry than to prose and perhaps that’s why I find it so much more enjoyable than trying to crank out another novel. There is also the fact that visual art has an obvious greater immediacy than a novel: what you see is what you get.

Because books have been a major part of my life for such a long time, it’s hard to let go, and that’s one reason why I decided to make an art zine combining visual art with fragments of my own poetry. For me, this is the perfect way to retain the literary while working in the medium of visual art.

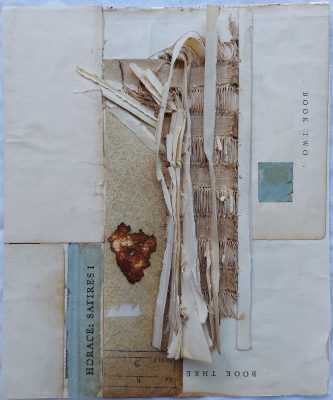

These days I spend more time taking books apart than writing them, but I still enjoy the physicality of books, and even when I’m destroying a book I’m doing so creatively, exploring its physical possibilities, its aesthetic qualities.

I haven’t entirely binned off the idea of writing a third novel, but this time it will be at my own (very slow) pace and on my own terms. There’s the very real possibility that, even if I do manage to finish it, it will never be published; but that no longer matters as much as it would have done a few years ago. My relationship with books and with literature is such that books will always be a part of my life in some form or other, but the passion for writing that sustained me through my teens and twenties is long gone. I’m just incredibly grateful that I’ve found a different way of being creative that brings me joy rather than dejection.

The works of Helen Kitson are physical ‘collages’ or collections of ephemera and found items.

Do you like this artist?

If so, why not write a comment or share it to your social media. Thanks in advance if you can help in this way.