Interview

Interview: Josephine Birch

In conversation with UK artist and educator Josephine Birch about her process and work.

Can you talk about your journey into or interest the arts?

When I was growing up my mum was a dress maker and textiles teacher and my sister, 9 years older than me, a painter, so the house was always filled with fabrics, canvases, half made dresses. It was kind of inevitable. I loved drawing and my mum was very encouraging, putting my copies of Monet on the wall, and talking to me about why they worked. Looking back I was very lucky in that sense. Initially I wanted to be a painter and moved to London to study painting at Wimbledon. Immediately I realised that my surroundings were really important and whilst I loved London, I couldn’t live it. I spent a lot of time quietly working in the print room at Wimbledon, teaching myself drypoint, and completely abandoned painting. I even gave away all my oil paints (though I do paint now).

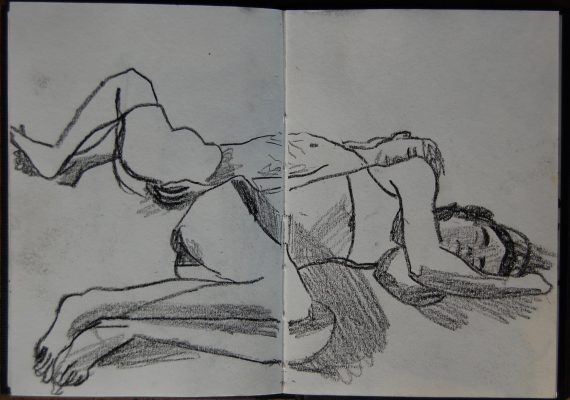

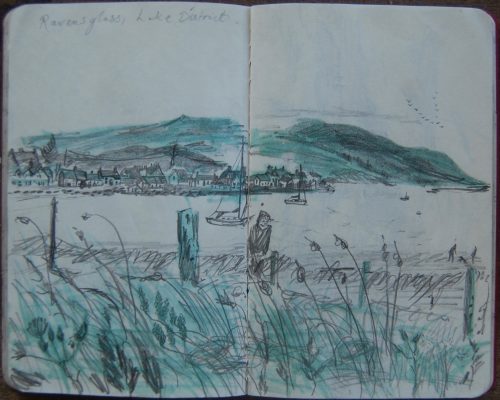

I was told my work was illustrative (with very negative connotations), so I did some research and found the Illustration BA at Cambridge School of Art where drawing was paramount and the first month at least, was spent drawing on location. This is what I had been looking for. The course was wonderfully broad, so you could experiment with more conceptual ideas but have a firm base in design, printmaking and skills based learning. I loved it there and it totally changed the way I worked, putting sketchbooks and drawing on location at the forefront of my practise. Subsequently, I was offered a place at the Royal Drawing School at the same time as getting a place on the Children’s Picture Book MA at CSA. I wasn’t expecting either! Both RDS and my MA helped to ferment ideas around imagination and narrative work whilst incorporating my sketchbook work from life which remains a firm part of my practise; a ballast.

Can you talk about how you use a sketchbook or journal? I know this might sound obvious, but the sketchbook is I suspect more than simply a set of pages. It is a contained book, often in chronological order, and it contains more than just drawings.

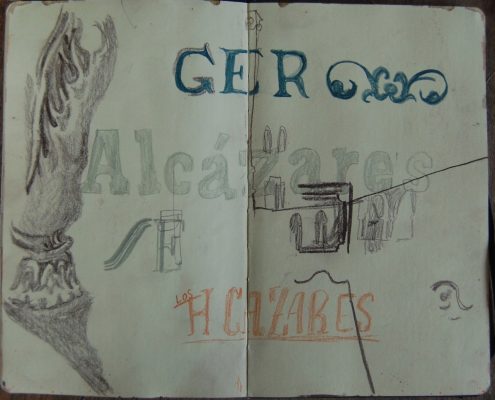

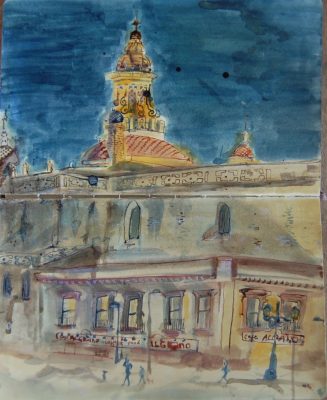

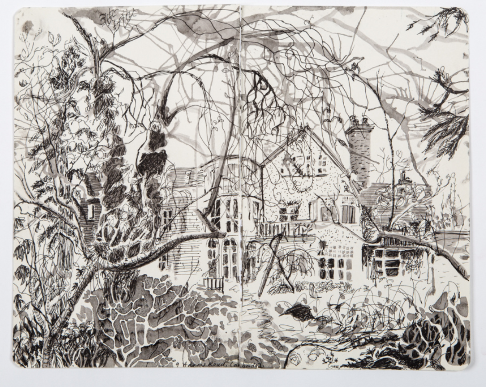

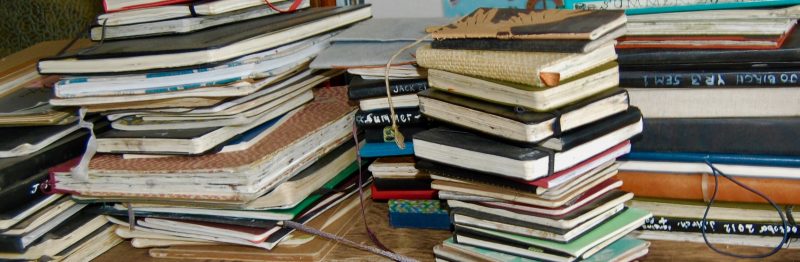

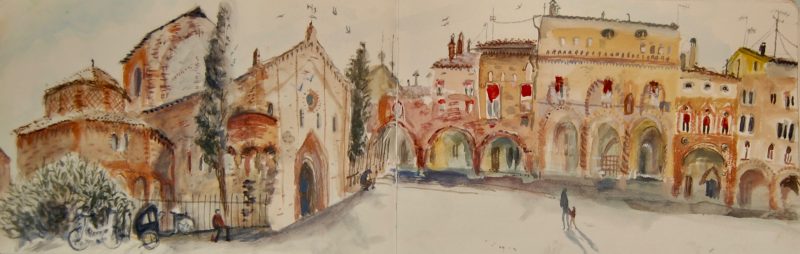

I have different sketchbooks for different things really, because I have to compartmentalise my different approaches. I have ADHD and it definitely means I jump, like a child in a toyshop, from one thing to another with great enthusiasm, so I have to keep these ideas organised to be able to return to a focus. I usually have a scrappy cheap one with notes, ideas, diary entries, dates. Then I have ones for picture book work; characters, storylines, experiments with materials and so on. Many drawings for Selkie came directly from my sketchbooks. Then I have my location drawing sketchbooks, always at least 3 different sizes depending on what I’m doing; i.e one in my pocket for a day trip or an a3 book when I’ve got my bag packed specifically for a day of drawing. The most beautiful thing about these sketchbooks (which I date on the spine) is that they are full of memories; it acts as a direct link to a place, the smells, people, and conversations. The drawings are my own personal experiences, the things I found fascinating, so the entire thought process of making a piece is imbued in each page, like picking up a lemon on the street in Seville, cutting it open and printing it in my sketchbook or talking to friends over a pint in the pub whilst drawing them.

Do you find the act of creating cathartic or even therapeutic to keep?

Definitely, as I mentioned working with ADHD can be tough, but the one time I genuinely sit still and completely focus is when I’m drawing. Its like a spell; I realise hours have past and I’m still doing one thing, like a form of meditation. Other thoughts come and go, passing by but my focus remains the same. That was an amazing discovery. Drawing is now, more than ever, a revolutionary act, because it is stillness, concentration, physical and cognitive connection to the world, in a time of digitalisation and screen time which can create absence in experience. The sketchbook is also a place of complete safety; a personal space to try things out, experiment and draw in different ways. This is hard to pass onto students who have had a lifetime of testing, box ticking and results based achievement- that the sketchbook is just for you, not to be marked, assessed, examined but utilised, explored and enjoyed.

Can you talk about your process of working. How do you work, how often?

The best way for me to get into working is to start first thing, before breakfast, even if its just sitting down with some research, or flicking through sketchbooks, it sets my brain into gear. I’m most focused when outdoors, drawing from life. When I do work I work fast, so it makes sense for me to use processes which put a space between my thinking and the making of the piece; I take my sketchbooks into the print room and work directly from them and this is when ideas can flow, because I am forced to slow down by the nature of the process. It’s a good balance for my brain. I would say I draw in my sketchbook most days, even if it’s just a quick sketch of the dog.

Your work often references nature and you clearly have an interest in the recycled or sustainable. Are these things all interrelated? You also reference literature, Ted Hughes for example, is that a big influence of your work?

I am very tied to the natural world, but I do also love city scapes, particularly the edges of urban space, like city parks, canal paths, industrial areas or bird life in urban centres. I live in a very rural part of Devon now, and spend a lot of time outdoors so it makes sense that this is part of my making too. Working on location is an on-going challenge, which I relish; changing weather, changing light, large views to make sense of. And yes, of course, it makes you very aware of wanting to protect the natural world and work in a sustainable manner. I don’t use acrylic paints for this reason and am engaged in on-going research on more sustainable ways of printmaking.

I’m always conscious of the privilege of living here and that it isn’t an experience everybody gets to have; this is particularly important when I’m thinking of picture books so often my ideas are based in green semi-urban spaces, a bit like where I grew up. I’m very interested in how living with wild or green spaces inform the way we think and, as Sara Maitland describes in Gossip From the Forest, there is symbiosis between storytelling and landscapes, and how the stories we tell are inspired by the land (specifically the forest) and that in turn effects the way we see, maintain and use outdoor/wild spaces, such as parks and gardens. Books like Tom’s Midnight Garden, and The Secret Garden were always favourites and literature has always inspired my work, sometimes directly, like with Ted Hughes and sometimes indirectly – a book, or poem will trigger something, like a way of seeing. It’s very important to my process and often on my mind even if it isn’t obvious in the work.

How do you feel about sharing your work online, can you talk about the sense of community, especially in these times, that this might bring?

Sharing work online is a double edged sword. I refused to engage with it for a long time, until friends hassled me into Instagram when I finally bought a smart phone. On the whole, that’s been excellent. I’ve found work through it, linked up with interesting creatives and its an easy way to share work. That being said, it is also a strain. I often share work too soon and feel a pressure to make works that will be good enough for sharing, so I’m getting better at keeping some work to myself, much like a sketchbook practise. There is a strong sense of community online right now with initiatives like Paper Patrons and The Artist Support Pledge. During lockdown I’ve used video calls (previously an alien concept to me) to make portraits and then turned them into a series of phone sized prints. I was recently talking with a colleague about how, since lockdown, artists have been forced to work digitally and on a smaller scale, in some ways similar to the British war artists who had to work with smaller canvases and less paper. It’s always interesting to see how artists naturally adapt their work to the times, and particularly important when engaging the public with a collective experience.

You have produced some Silent Book works. Can you talk more about this?

I am very interested in silent books (wordless picture books) and what they can do for readers. I love that they can span reading abilities and language barriers. Bilingual parents have told me they love Selkie because they can read it to their child in their respective languages. Also, though I love to write, I find it easier to come up with stories through pictures, so I work well if I’m given someone else’s text, but if I write my own I find it hard to create distance and make artworks that deliver something new, something original that enlivens the text instead of just mirroring it.

What I adore about picture books is that they are art for all. Pages and pages of beautiful artworks, pushing boundaries and social norms, in the home, in schools, in libraries, accessible to the masses and to families of all description, in a way other arts can struggle to be.

Josephine teaches printmaking, art and design at a HE/FE college and is an associate artist at Coombe Farm Studios. She is currently working on a series of books, The Other Stories with writer/producer Emma Bettridge amongst many other projects.

Do you like this artist?

If so, why not write a comment or share it to your social media. Thanks in advance if you can help in this way.